[Spoilers for this issue.]

The Anxiety of Influence is strong in this one. Here we have

Gerard Way, an enthusiast and descendent of Grant Morrison’s oeuvre, writing a

series Morrison defined. Leaving your mentor’s shadow is difficult enough, even

when you don’t cover their songs. But have no fear, Doom Patrol #1 promises hipness and weirdness enough to rival

Morrison, without aping Morrison.

No overall plot presents itself, yet. The vines have

sprouted separately, but will, likely, intertwine as they grow. Our focal

character, Casey Brink, bursts onto the page, swerving an ambulance. Her

partner contemplates universes living in his gyro. A cyborg trudges across an alien desert. Extra-terrestrials

run fast food. And what’s going on with Niles Caulder?

|

| Behold: a synecdoche |

The first page synecdochises the issue. Four unconnected

panels in bisected colours and contents – two blue, two red, two of victory and

tenderness, two of destruction – intrigue the reader. Dialogue captions overlay

them, a continuous element atop discrete images. While the issue’s plotlines

stand far apart, the page implies a continuous element spans them.

The issue introduces multiple characters, of whom we see

only broad outlines, but interesting outlines. Casey Brink is an altruist one

step removed from day-to-day reality. Robotman trudges onto screen as a no

nonsense tough-guy; a tad cliché, but still charming. And Terry None, well,

I’ll let you find out.

Readers of Morrison’s run will have a stronger grip on

what’s happening than new-comers. For one, they’ll recognise a few characters.

Initiates to Doom Patrol need not

fear; continuity won’t lock them out. The gaps in a new-comer’s knowledge are

not frustrating, rather, they are mysterious.

The tone is urban-fantasy-cum-magical-realism. I don’t say

this for pretension. While I cannot call Doom

Patrol #1 pure magical realism – its fantastical elements are far too overt

– it has what I consider essential to magical realism: deadpan delivery. In Doom Patrol, characters treat fantastical

elements as though they lay within the realm of probability. Events are

strange, but characters don’t feel the impossible has intruded on their world.

Imagine you walked home one night and saw a man flamethrowing the gutters. He

must have a good reason, you think, before walking away. Before you saw it, you

never even considered it happening, yet seeing it, you accept it. Doom Patrol’s characters accept the

world like this. They see a robot stumbling through an alley, and, yeah, it

weirds them out, but they accept it.

Gerard Way injects urbanity with half-ironic mythic-ness. One

the series’ first lines is: ‘… what we are trying to do here is preserve the

precious life force bestowed upon this gentle soul by the almighty mother-womb…’

Although said in jest, it sets the issue’s tone. A tone furthered by that same

speaker’s ruminations on the universes contained within his gyro. He then bins the gyro. In this way, Way almost vaccinates

the series against accusations of pretention, as though he mocks the navel

gazing. But soon an explosion confirms these ruminations on the gyro-cosmos. While Way delivers these

mythic moments with a wink, he does not succumb entirely to irony by dismissing

mythic-ness altogether. The series occupies a ‘hipness’ on the edge of irony

and sincerity; the irony merely acknowledges the seeming silliness of the

sincerity.

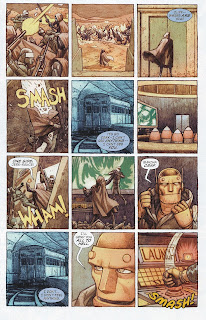

Counter-intuitively, depicting disorder requires a orderly

craftsman. Nick Derington keeps disciplined page layouts. Nearly every page is

a simple, panel-and-rows arrangement of rectangular panels. Rarely do panels

overlap, or take on exotic shapes. As most pages maintain white gutters between

the panels, those few times the illustrations bleed into the gutters make big

moments resonate more.

|

| one that bleeds into the gutters |

My few criticisms of this issue regard how the series proper

might fail. This opening gives us

plenty of plot threads, but will Way weave them into a whole? Will that whole

exceed mere flash and style? Will Way’s deepest theme be a rather shallow

critique of the fast-food industry? Will this run just be a Hot-Topicfication

of Morrison’s Doom Patrol, a surface-level homage with a millennial sheen?

These worries are legitimate, but I’ve faith in Way; his previous Umbrella Academy comics stick a similar

landing.

While those concerns regard the future, I do question a

fundamental aspects of this book. As Noah Berlatsky wrote at The Atlantic, Morrison’s Doom Patrol focused on outcasts. Not assimilating outcasts, like

Superman the space refugee; no, those who were perpetual outcasts, by

circumstance and choice. Something prevented Morrison’s Doom Patrol from

‘fitting in’ with conventional society. Most of Way’s characters may be

outcasts, but they seem able to fit in. Side characters may describe Casey

Brink as ‘weird’, but she could blend

with normal people, unlike, say, a monkey faced teenaged girl. There is a

narrative utility to this; it gives us, most likely insiders, a way into the

madness of Doom Patrol, someone like

us to bridge the gap. But should the series accommodate us normies? Shouldn’t

Way throw us in, to see how these unassimilate-able outcasts function in the

world? Though, perhaps, this is one way Way aims to differentiate his run from

his mentor’s.

Doom Patrol #1 is a superb first issue. It

dangles mysteries, and thrills in the meantime. Buy it.

[Images scanned from DC's Young Animal's Doom Patrol #1, written by Gerard Way, illustrated by Nick Derington, coloured by Tamara Bonvillain, and lettered by Todd Klein.]

No comments:

Post a Comment